Sean Heather

Sean Heather

Senior Vice President, International Regulatory Affairs & Antitrust, U.S. Chamber of Commerce

Published

April 26, 2022

All hat, no cattle is a well-known saying among ranchers to describe someone that is all talk and no substance. The saying seems more than appropriate this week as rising beef prices will be the focus of multiple hearings on Capitol Hill where some policymakers are expected to push the discredited claptrap that high food prices are caused by corporate greed and industrial concentration.

Yet, no one with a basic understanding of economics believes this is true – not the White House staff, not the Democratic Party’s leading economists, not the USDA’s data analysts, not the Washington Post, and certainly not the American people.

Even a cow understands, at some level, the principle of scarcity: supply shocks, such as a lack of rain, paired with high demand, say the birth of new calves, means that grass will become harder to find. That, in a nutshell, explains higher food prices—increased demand, COVID-related supply chain disruptions, and higher input costs, especially energy and labor.

President Biden’s own Agriculture Department recognizes that, “[h]igh feed costs, increased demand, and changes in the supply chain have driven up prices for wholesale beef and dairy.” Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, a senior official in both the Clinton and Obama Administrations, has explained that macroeconomic trends are raising prices around the globe.

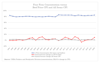

Indeed, a smidgen of bovine common sense puts the lie to “all hat” narrative that corporate concentration is to blame. Government data shows that concentration in the meat packing sector has remained constant for the past 25 years.

In fact, since 2007, the economy has become less concentrated. Meat prices fell in the five years before the pandemic. If, as the administration asserts, industrial consolidation has been a problem for years and is driving the current surge in prices, then why didn’t it drive prices higher before?

The answer, of course, is politics. This winter, “at least four Democratic polling experts told senior White House officials that they needed to find a new approach as public frustration over price hikes became widespread and highly damaging to Biden’s popularity … ‘You need a villain or an explanation for this. If you don’t provide one, voters will fill one in.’”

The White House’s cynical messaging is giving its own partisans stomach aches. “Senior officials at the Treasury Department, for instance, have been unsettled by the White House’s attempts to blame some large corporations for inflation, skeptical of that explanation for the recent rise in prices.” In a recent piece titled, “The White House once again offers a bizarre message on inflation,” the Washington Post explains:

“President Biden is facing mounting criticism for inflation’s rise to its highest level since 1982. Unfortunately, the White House’s latest response is to blame greedy businesses. Economists across the political spectrum are rightly calling out the White House for this foolishness. Even some within the White House are questioning this approach.”

Rather than blame American business, policymakers should explore other avenues to encourage competition and lower prices for consumers. Former Secretary Summers may not own a ranch, but he deserves a hat tip for suggesting policymakers should work to reduce tariffs, raise supplies of fossil fuels, encourage people to return to work, and relax regulations. All these tools, along with sensible monetary policy, would allow the business community to serve the needs of consumers more efficiently and at lower prices.

About the author

Sean Heather

Sean Heather is Senior Vice President for International Regulatory Affairs and Antitrust.