Table of Contents

Europe remains the most attractive region in the world for U.S. companies investing abroad.

Despite an array of pressures in 2022, the eurozone economy managed to grow faster than either the U.S. or Chinese economies. This year Europe continues to face Russia- induced energy shocks, ongoing war, inflationary concerns, and the backup in global interest rates. Many European economies have demonstrated surprising resilience in the face of these challenges. Nonetheless, the economic outlook is fluid and uncertain.

-

$4 trillion

Total U.S. FDI stock in Europe (2021)

-

61.5%

of total U.S. global investment

Europe’s economic performance is important to the United States for the simple reason that on a global basis, no region of the world offers more opportunities in terms of market size and wealth, and access to skilled resources, than Europe. And outside the United States, no region has more sway on corporate America’s bottom line than Europe. Europe remains the most attractive region in the world for U.S. companies investing abroad.

The latest investment figures underscore corporate America’s enduring commitment to its long-standing transatlantic partner. Measured on a historic cost basis, the total stock of U.S. FDI in Europe was $4 trillion in 2021, or 61.5% of total U.S. investment abroad. This is almost four times the amount of comparable U.S. investment in the Asia-Pacific region ($957 billion).

According to the latest figures from the United Nations, while FDI inflows to both the United States and Europe were severely affected by the global recession of 2020, flows have since rebounded. Global FDI flows to Europe totaled just $81 billion in 2020, down from $404 billion in 2019. These sharp swings in global FDI to Europe were driven mainly by large divestments and negative intra-company loans in the Netherlands and Switzerland, and the general downdraft related to the pandemic. However, these drops were one-offs. Global FDI flows to Europe rebounded to a $219 billion in 2021, accounting for nearly 14% of total global inflows. Figures for 2022 are not available but we suspect FDI flows to Europe built off the gains of 2021.

This overall number, while impressive, does not tell us much about the reasons for such investment or the countries where U.S. companies focus their investments. As we have stated in previous surveys, official statistics blur some important distinctions when it comes to the nature of transatlantic investment flows. Recent research, however, helps us understand better two important phenomena: “round-tripping” and “phantom FDI”.

Round-Tripping

Round-tripping investments go from an original investor, for instance in the United States, to an ultimate destination in a country such as Germany, but flow first from the United States to an intermediate country such as Luxembourg, and then from Luxembourg to Germany. Official statistics record this as a U.S.-Luxembourg flow or a Luxembourg-Germany flow. While Luxembourg may derive some economic benefit from that flow emanating originally from the United States, the ultimate beneficiary is in Germany. Applying this example to 2017, the year with the most recent data, official figures from the IMF indicate that FDI in Germany from the United States was around $90 billion, whereas research by economists at the IMF and University of Copenhagen that took account of these “round tripping” flows concluded that the stock of “real FDI” from the United States in Germany was actually almost $170 billion. Similarly,“realFDI”links from Germany to the United States are considerably higher than official statistics might indicate. All told, they estimated that “real FDI” bilateral links from Germany to the United States in that year topped $400 billion in 2017, whereas official statistics put that figure closer to $300 billion.

This phenomenon continues to apply to these and other important bilateral investment links, such as those between the U.S. and the UK or the U.S. and France. In these and other instances, “real FDI” links are likely to be higher than standard measurements indicate.

“Phantom” vs. “Real” FDI

The second important phenomenon is what economists call “phantom FDI,” or investments that pass through special purpose entities that have no real business activities. To understand the nature of transatlantic investment links, it is important to be able to separate phantom FDI from FDI in the “real” economy. Damgaard, Elkjaer and Johannesen estimated that investment in countries such as Poland, Romania, Denmark, Austria and Spain, for instance, were mostly genuine FDI investments, while investment in countries such as Luxembourg and the Netherlands were largely comprised of investments in corporate shells used to minimize the global tax bills of multinational enterprises. They estimated that most of the world’s “phantom FDI” in 2017 was in a small group of well-known offshore centers: Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Singapore and the Cayman Islands.

U.S. holding companies have played an important role in the rise of U.S.-Europe FDI over the past few decades. As of 2020, the last year of available data, nonbank holding companies accounted for $2.9 trillion, or about 47% of the global U.S. outward FDI position of approximately $6.2 trillion, and 54% of total U.S. FDI stock in Europe.

As the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis notes, “The growth in holding company affiliates reflects a variety of factors. Some holding- company affiliates are established primarily to coordinate management and administration activities – such as marketing, distribution, or financing – worldwide or in a particular geographic region. In addition, the presence of holding company affiliates in countries where the effective income tax rate faced by affiliates is relatively low suggests tax considerations may have also played a role in their growth. One consequence of the increasing use of holding companies has been a reduction in the degree to which the U.S. Direct Investment Abroad position (and related flow) estimates reflect the industries and countries in which the production of goods and services by foreign affiliates actually occurs”.

Tables 1a and 1b, drawing on BEA data, reflect the significance of holding companies in the composition of U.S. FDI outflows. European markets accounted for roughly 58% of total U.S. FDI outflows between 2009 and 2020. However, when flows to nonbank holding companies are excluded from the data, the share of outflows to markets such as Europe and Other Western Hemisphere declines. In 2020, U.S. FDI flows to holding companies in Europe rebounded sharply to $62.8 billion. This represented over half of total U.S. FDI outflows to Europe. In prior years, FDI outflows to Europe were negative (-$189 billion in 2018 and -$87 billion in 2019), as U.S. companies repatriated a large amount of accumulated foreign earnings.

In the long run, when FDI related to holding companies is stripped from the numbers, the U.S. foreign direct investment position in Europe is not as large as typically reported by the BEA. Nonetheless, Europe remains the destination of choice among U.S. firms even after the figures are adjusted. Between 2009 and 2020, Europe still accounted for over half of total U.S. FDI outflows when flows from holding companies are removed from the aggregate. Europe’s share was still more than double the share to Asia, underscoring the deep and integrated linkages between the United States and Europe.

Since 2017, however, the role of offshore financial centers has gradually declined, while that of large economies, particularly the United States, has increased. One contributing factor is likely to have been the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018, which lowered incentives to keep profits in low-tax jurisdictions and led to a substantial U.S. repatriation of funds from foreign subsidiaries. Additionally, some flows to offshore financial centers are likely to have been blunted by sustained international efforts to reduce tax avoidance, like the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative, which has led 137 countries to reach agreement on a fair allocation of taxing rights and a global minimum effective tax at a uniform tax rate of 15%.

In the aggregate, and extrapolating forward, about 54% of America’s total FDI position in Europe was allocated to non-bank holding companies in 2020, meaning that less than half of the $3.7 trillion was invested in “real economy” industries such as mining, manufacturing, wholesale trade, finance, and professional and information services. Excluding holding companies, total U.S. FDI stock in Europe in 2020 amounted to $1.7 trillion – a much smaller figure.

Table 2: U.S. FDI Flows to Europe ($Millions, (-) inflows)

| Country | 1990-1999 | 2000-2009 | 2010-3Q2022 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $ Aggregate Total | % of Total Europe | $ Aggregate Total | % of Total Europe | $ Aggregate Total | % of Total Europe | |

| Europe | 465,337 | 1,149,810 | 1,889,346 | |||

| Austria | 2,908 | 0.6 | 501 | 0 | 8,790 | 0.5 |

| Belgium | 12,028 | 2.6 | 40,120 | 3.5 | 28,757 | 1.5 |

| Czech Republic | 155 | 0 | 1,941 | 0.2 | 5,400 | 0.3 |

| Denmark | 2,798 | 0.6 | 5,782 | 0.5 | 11,730 | 0.6 |

| Finland | 1,485 | 0.3 | 1,598 | 0.1 | 3,982 | 0.2 |

| Germany | 31,817 | 6.8 | 60,363 | 5.2 | 76,678 | 4.1 |

| Greece | 413 | 0.1 | 943 | 0.1 | 369 | 0.1 |

| Hungary | 2,929 | 0.6 | 1,376 | 0.1 | 838 | 0 |

| Ireland | 21,369 | 4.6 | 115,085 | 10 | 368,284 | 19.5 |

| Italy | 13,825 | 3 | 26,462 | 2.3 | 20,459 | 1.1 |

| Luxembourg | 15,192 | 3.4 | 126,989 | 11 | 334,043 | 17.7 |

| Netherlands | 70,770 | 15.2 | 295,889 | 25.7 | 361,771 | 19.1 |

| Norway | 4,198 | 0.9 | 4,997 | 0.4 | 17,480 | 0.9 |

| Poland | 2,681 | 0.6 | 4,699 | 0.4 | 4,613 | 0.2 |

| Portugal | 1,993 | 0.4 | 2,212 | 0.2 | 876 | 0 |

| Russia | 1,555 | 0.3 | 11,289 | 1 | -3,756 | -0.2 |

| Spain | 11,745 | 2.5 | 28,371 | 2.5 | 15,552 | 0.8 |

| Sweden | 10,783 | 2.3 | 16,974 | 1.5 | 7,702 | 0.4 |

| Switzerland | 32,485 | 7 | 97,869 | 8.5 | 130,258 | 6.9 |

| Turkey | 1,741 | 0.4 | 5,994 | 0.5 | 9,706 | 0.5 |

| United Kingdom | 175,219 | 37.7 | 237,906 | 20.7 | 444,751 | 23.5 |

| Other | 17,465 | 2.6 | 19,487 | 1.4 | 2,927 | 0.2 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data as of January 2023.

These figures illustrate the extremely volatile nature of U.S. FDI annual outflows. Table 2 provides a more long-term view of U.S.-European investment ties. As shown in the chart, the share of U.S. FDI in both Germany and France declined sharply this past decade, with France accounting for just 1.5% of U.S. FDI flows to Europe from 2010 through the third quarter of 2022. Germany’s share is slightly higher, 4.1%, but still off the levels of previous decades. However, as mentioned, these figures need to be interpreted very carefully, since a good deal of original investment from the United States makes its way to France and Germany via other countries, and analyses that include “round-tripping” estimates conclude that U.S. FDI that eventually ends up in France and Germany remains robust.

Ireland has become a favored destination for FDI among U.S. companies looking to take advantage of the country’s flexible and skilled English- speaking labor force, low corporate tax rates, strong economic growth, membership in the European Union, and pro-business policies. Even when adjusting U.S. FDI figures to take account of flows of U.S. holding companies, Ireland still ranks as one of the most attractive places in the world for U.S. businesses.

and differentiated by country. Different growth rates, differing levels of consumption, varying degrees of wealth, labor force participation rates, financial market development, innovation capabilities, corporate tax rates – all of these factors, and more, determine where and when U.S. firms invest in Europe.

Table 3 underscores this point. The figures show U.S. affiliate sales from a given country to other destinations, or the exports of affiliates per country. Of the top twenty global export platforms for U.S. multinationals in the world, nine are located in Europe, a trend that reflects Europe’s intense cross- border trade and investment linkages and the strategic way U.S. firms leverage their European supply chains. For U.S. companies, Ireland is the number one platform in the world from which their affiliates can reach foreign customers. Switzerland, ranked third, remains a key export platform and pan-regional distribution hub for U.S. firms.

On a standalone basis, U.S. affiliates’ exports from Ireland are greater than the total export volumes of most countries. Such is the export-intensity of U.S. affiliates in Ireland and the strategic importance of Ireland to the corporate success of U.S. firms operating in Europe and around the world. Moreover, the UK’s exit from the EU may further solidify Ireland’s spot as the number one location for U.S. affiliate exports. When exporting from the UK, new barriers to trade, including regulatory checks and rules of origin requirements, in addition to stricter immigration rules, could cause some companies to relocate operations to Ireland in search of easier access to the EU market.

The UK still plays an important role for U.S. companies as an export platform to the rest of Europe. However, the introduction of the euro, the Single Market, EU enlargement and now Brexit have enticed more U.S. firms to invest directly in EU member states. The extension of EU production networks and commercial infrastructure throughout a larger pan-continental Single Market has shifted the center of gravity in Europe eastward within the EU, with Brussels playing an important role in shaping economic policy.

Why Europe Matters

The cyclical challenge before Europe is substantial: Russia’s war and energy shocks will exert considerable pressure on many economies. Consumers and businesses have been hammered by the spike in energy costs, although diversified supplies and public support mechanisms, along with falling prices, have helped alleviate some of the burden.

That said, it is important to see the forest from the trees, and to recognize that, first, Europe on a standalone basis remains one of the largest and wealthiest economic entities in the world and, second, the region remains a critical cog in the corporate success of U.S. firms.

Europe is home to more than 500 million people across the EU, the UK, Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and a host of eastern countries. This cohort accounted for roughly 23% of world output in 2021 – slightly lower than the U.S. share of 24%, but greater than that of China’s (18%). On a purchasing power parity basis, Europe’s share was greater than that of the United States but less than that of China in 2021.

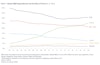

Given its size, Europe remains a key pillar of the global economy and critical component to the corporate success of U.S. firms. As Table 4 highlights, Europe attracts more than half of U.S. aggregate FDI outflows. The region’s share of total U.S. FDI during the last decade was 57.3%, which is up from the first decade of this century as well as from the level of the 1990s. We are early in this decade, but thus far, Europe’s share of U.S. FDI outflows has actually increased to 64.3% of the total. Part of this dynamic reflects weakening U.S. investment flows to China.

Even after adjusting for FDI flows related to holding companies, Europe remains the favored destination of U.S. firms. This runs counter to the fashionable but false narrative that corporate America prefers low-cost nations in Asia, Latin America, and Africa to developed markets like Europe.

Investing in emerging markets such as China, India, and Brazil remains difficult, with indigenous barriers to growth (poor infrastructure, dearth of human capital, corruption, etc.) as well as policy headwinds (foreign exchange controls, tax preferences favoring local firms) reducing the overall attractiveness of these markets to multinationals. As shown in Table 5, there has been a wide divergence between U.S. FDI to the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China) and U.S. FDI to Europe. After a drop in flows to Europe in 2019 due to U.S. domestic tax reform, investment in Europe rebounded in 2020 and continued to gather momentum in 2021 and 2022. In the first three quarters of 2022, U.S. FDI outflows to Europe totaled roughly $172 billion, 29 times more than U.S. FDI outflows to China of $6.1 billion and 10 times more than U.S. FDI outflows to in flows to the BRICs of $16.5 billion.

Gaining access to wealthy consumers is among the primary reasons why U.S. firms invest overseas, which explains the continued attractiveness of affluent Europe to American companies. Fourteen of the twenty-five wealthiest nations in the world are European. GDP per capita in the EU ($38,234 in 2020) is significantly higher than that in China ($12,556) or India ($2,277).

Wealth drives consumption, with the EU+UK accounting for roughly 21% of global personal consumption expenditures in 2021. That’s a lower share than that of the U.S. (30%) but well above that of China (12%), India (3.4%) and the BRICs combined (18.6%). Since 2000, personal consumption expenditures in the EU have almost doubled to roughly $9.6 trillion, representing an increasing market opportunity for large global corporations.

Wealth in Europe is also correlated with a highly skilled and productive workforce, advanced innovation capabilities, and a world-class R&D infrastructure – underpinning the attractiveness of the EU to corporate America. The EU’s labor force is not only more than twenty percent larger than America’s; its labor force participation rate is more than ten percentage points higher (74.3%) than it is in the U.S. (62.4%). Finally, when it comes to skilled labor, Europe again leads the United States. To this point, in 2018, the last year of available data, the number of science and engineering graduates in the EU+UK totaled roughly 1 million, versus 760,000 in the U.S., according to the National Science Foundation. Since the U.S. economy is short of technology and scientific talent, accessing Europe’s tech talent pool is critical to the long-term success of many American firms.

Drivers of foreign investment into Europe

- Access to a large market

- Purchasing power of consumers

- Skilled and productive workforce

- Advanced innovation capabilities

- World-class R&D infrastructure

- Business-friendly policies

- Respect for the rule of law

- Strong financial markets

Business-friendly policies surrounding property rights, the ability to obtain credit, employment regulations, starting a business and cross-border trade have been a major draw for foreign investors over the years. According to the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) latest World Competitiveness Rankings for 2022, fourteen European economies ranked in the top twenty-five. Among the top ten, Denmark was ranked #1, followed by Switzerland (2), Sweden (4), the Netherlands (6), Finland (8) and Norway (9). Other factors, such as shared values, respect for the rule of law, credible institutions, advanced infrastructure, and strong financial markets continue to set Europe apart when it comes to U.S. business investment.

Finally, Europe continues to be a world leader when it comes to innovation and knowledge- based activities. According to the 2022 Global Innovation Index, eight European economies rank among the top 15 most innovative countries in the world (Table 6). The index takes into account a wide range of factors such as institutions, education quality, research & development, information & communication technologies (ICT) infrastructure, and more.

A related measure of knowledge-based capabilities is science & technology (S&T) intensity – or the sum of the patent and scientific publication shares divided by the population. By this measure, many European and U.S. regions have more scientific output per capita than their Asian counterparts. In fact, of the top 15 science & technology clusters, ranked by S&T intensity, 7 are located in Europe, 6 in the United States, and only 2 are in Asia (Table 6).

Since R&D expenditures are a key driver of value- added growth, it is interesting to note that EU- and UK-based organizations accounted for slightly more than one-fifth of total global R&D in 2020 in purchasing-power parity terms. That lagged the share of the United States and China but exceeded the share of Japan and South Korea. Over the past two decades, China has steadily advanced its R&D capabilities, and is projected to overtake the United States as the top R&D spender in the world (Table 7).

Add it all up and Europe – large, wealthy, competitive, and well-endowed with a large pool of skilled labor – remains a formidable economic entity with a great deal of upside.

Europe remains a leader in a number of cutting-edge industries, including life sciences, agriculture and food production, automotives, nanotechnology, energy, and information and communications. Innovation requires talent, and on this basis, Europe is holding its own relative to other parts of the world. Europe is the world leader in terms of full-time equivalent research staff. Of the world’s total pool of research personnel, the EU plus the UK, Switzerland, Norway and Iceland housed an estimated 2.3 million researchers in 2019, versus 1.6 million in the United States and 2.1 million in China, according to OECD estimates.

Finally, Europe is home to one of the most educated workforces in the world. In countries such as Ireland, Switzerland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands, the share of the working age population with a bachelor’s degree or higher exceeds 40%. The comparable figure for the U.S. is 39%. While U.S. universities remain a top destination for foreign students, the UK, Germany and France are also notable attractions. In the end, Europe remains among the most competitive regions in the world in terms of science and technology capabilities. The U.S. National Science Board has explicitly recognized EU research performance as strong and marked by pronounced intra-EU collaboration.

The Bottom Line

These are very challenging times for Europe. The near-term economic outlook remains fraught with risks and uncertainty as the continent struggles with war and its consequences. Slower growth and/or a recession in Europe is a significant risk to U.S. firms. However, an even greater risk to corporate America is being absent from the continent. In an age of scarce workers, resources, and markets, Europe has never been more important to American businesses.

Add it all up and Europe – large, wealthy, competitive, and well-endowed with a large pool of skilled labor – remains a formidable economic entity with a great deal of upside. Past and future, America’s transatlantic partnership with Europe continues to yield significant dividends.