J.D. Foster

J.D. Foster

Former Senior Vice President, Economic Policy Division, and Former Chief Economist

Published

May 25, 2017

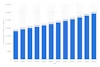

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the federal deficit to exceed well over half a trillion dollars in fiscal year 2017, nearly tripling by 2027, and climbing steadily thereafter. CBO further projects publicly held debt to average nearly $15 trillion this year, rising to nearly $25 trillion over the next 10 years. As a result, later this year Congress will once again be called on to raise or suspend the debt limit. Given the nation’s fiscal plight, this might seem a strange time to consider abolishing the debt limit, but that is exactly what Congress should do.

Source:

https://www.statista.com/statistics/216998/forecast-of-the-federal-debt-...

The practical effect of the debt limit has been to manufacture a series of distracting and economically dangerous political crises.

Indeed, rather than leveraging congressional action toward deficit reduction, the practical effect of the debt limit has been to manufacture a series of distracting and ultimately economically dangerous political crises while achieving little to nothing with respect to the aspirational purpose of reining in debt. The debt limit as a political and policy device is obsolete, yet it is and will remain a danger to the nation’s financial markets and economy broadly until we disarm it.

The debt limit having been previously suspended, once again came into effect on March 15 of this year. Treasury then declared a “debt issuance suspension period,” resorting to well-established “extraordinary measures” and the positive cash flow typically enjoyed in April due to tax filing season. The Treasury is likely to lose its ability to muddle through waiting for congressional action sometime in late summer or early fall. Once again, a contrived and ultimately pointless crisis will be upon us.

The debt limit, or more accurately the threat of not raising the debt limit, has always been a dangerous tool of fiscal restraint, but it has not always been a useless one. Proponents leveraged the debt limit politically to pressure Congress into accepting the famous 1985 Gramm-Rudman-Hollings deficit control act which for a brief period managed to impose some additional deficit restraint. However, as the rise in the federal debt in the intervening years attests, the debt limit has created major political fights, and economic risks, with no apparent purpose.

Why has the debt limit proved such a poor tool of fiscal policy? Many factors may contribute, but two by far seem most important. The first is the sad reality that many in Congress and many Americans seem to care very little whether the federal government runs a balanced budget or a massive deficit. This is understandable, to a degree, as the federal government has for many years run massive deficits, now most conveniently expressed as fractions of a trillion dollars, with little apparent consequence. Interest rates remain curiously low and the economy grows, albeit slowly. There is no apparent urgency.

A man once jumped off the top of a tall building and as he passed each floor the onlookers would ask, “how’s it going?” to which the deluded man-bird would respond, “so far, so good.” It didn’t end well for the poor chap. Similarly, bad policy can often run for years before triggering an inevitable and painful response. In the mid-2000s housing prices rose and rose and the popular reaction insisted this it would continue because, after all, housing prices never fall. And then they fell, a lot. At some point, the federal government’s enormous debt load, too, will matter a lot..

One suspects most Members of Congress and most Americans understand that unsustainable fiscal policies such as the United States is now projecting truly are unsustainable. Even the minimally sagacious seeing misfortune ahead make adjustments, but so far little appetite appears for correcting America’s fiscal trajectory. President Trump’s recent budget submission showcasing a return to balance in a decade is the rare exception.

The debt limit should be abolished, or at least suspended for a very long time.

The second reason the debt limit is an ineffective tool for fiscal policy involves the debt limit’s appearance as something of an Armageddon weapon. What would really happen if the Treasury ran out of cash and at least in some technical sense defaulted on the nation’s debt? No one really knows, because we’ve never done it before, and this uncertainty camouflages the risks for those who do not want to change, allowing them to ignore the warnings regardless of how somber, shrill, or credibly they are given. Some are thus inclined to default on the debt, perhaps to make a point, recalling the Vietnam War era observation of a U.S. Major with respect to the town of Ben Tre in the Mekong Delta, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.”

The debt limit should be abolished, or at least suspended for a very long time, not because the U.S. fiscal picture is sanguine, but because it is far from it, and the debt limit has become an ineffective and dangerous tool that is at best a distraction from the pursuit of real fiscal remedies. Rather than waste time trying to once again dodge an economic bullet of possibly terrible consequences, Congress should focus instead on either on creating more effective, less dangerous budget tools or, better yet, restraining the deficit through long-ignored but ultimately inevitable entitlement reforms.

In any event, the debt limit is a tool best left on the scrapheap. This is one village we should just leave alone.

About the author

J.D. Foster

Dr. J.D. Foster is the former senior vice president, Economic Policy Division, and former chief economist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. He explores and explains developments in the U.S. and global economies.