Published

January 23, 2020

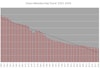

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on January 22 released its annual estimate of union membership in the United States. This year’s report showed that union membership slipped to 10.3 percent of the total workforce in 2019, which is the second consecutive decline of 0.2 percentage points from the prior year. The drop continues the steady, six-decade slide in membership that has been ongoing since the mid-1950s, and it represents the lowest union membership rate since the mid-1930s, notwithstanding a 1983 change in how these data are calculated. In addition to the lower membership rate, the total number of union members dropped to 14.6 million, an overall decrease of approximately 170,000.

Union membership in the private sector fell from 6.4 percent to 6.2 percent, and despite BLS’s characterization that it was “little changed,” public sector unionization dropped from 33.9 percent to 33.6 percent, which reflects a loss of just over 100,000 members. In any event, public sector unionization remains of over five times that of the private sector.

As has been the case for quite some time, nearly half of all union members work in the public sector, with the total number at 7.1 million versus 7.5 million in the private sector. The highest density of public sector unions also continues to be at the local level, which is 39.4% unionized, reflecting heavily unionized occupations, such as police officers, firefighters, and teachers.

In contrast to union membership, the number of workers represented under union contracts who were not union members rose from 1.6 million to 1.8 million. However, the total percentage of union-represented workers including non-members still declined slightly from 11.7 percent to 11.6 percent.

The union membership rate continues an ominous long-term trend that has organized labor leaders scrambling for solutions. During the Obama administration, their sympathetic political allies worked assiduously to reshape labor policy to help alleviate the hemorrhaging, and unions pumped millions of dollars into failed campaigns with front groups known as worker centers, albeit with little effect. As the graph above illustrates, membership in unions continued to decline steadily despite those efforts. Organized labor’s latest gambit is the so-called “Protecting the Right to Organize” (PRO) Act, a piece of legislation that would codify a slew of terrible policies designed to force more people into unions. At a time when the economy is humming along nicely, such a proposal would seem ill-guided at best, but, of course, labor leaders are laser-focused on solving their membership crisis. Rather than seek an introspective explanation for it, though, their solution now is a cynical proposal that would simply weaken the economy for all.

About the author

Sean P. Redmond

Sean P. Redmond is Vice President, Labor Policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.