Sean Heather

Sean Heather

Senior Vice President, International Regulatory Affairs & Antitrust, U.S. Chamber of Commerce

Published

February 23, 2021

Today, legislators and economists are actively debating the government’s role in reviewing mergers. However, this debate is largely driven by a misleading narrative that the courts, through judicial precedent, have made it almost impossible for government agencies to block problematic mergers.

Earlier this month, Carl Shapiro and Howard Shelanski, two respected progressive-leaning economists, released a study about the Judicial Reponses to the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines. The study unearthed some stubborn facts that clearly support the view that antitrust laws governing mergers work and work reasonably well.

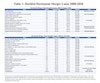

Shapiro and Shelanski examined horizontal mergers that were challenged by the antitrust agencies and litigated before the courts during two time periods, from 2000-2010 and from 2010-2020. The reason for looking at these two decades comparatively is that antitrust agencies updated their thinking in the 2010 Horizontal Mergers Guidelines. It’s worth noting that both authors played a significant role in revamping these guidelines during their time at the agencies and make the case in support of how the guidelines have shaped merger review.

Table 1 in the study unearths the dirty little secret about litigated mergers. In short, the government’s ability to block a merger is anything but inept.

Here are three ways this study undermines calls to significantly change our merger laws:

- It’s good to be the government! Surprise, the government generally wins when it brings forth a case to stop a merger. Looking at cases that were litigated during the first decade, the study shows the government won 9 out of 14 cases or 64% of the time. In the second decade the government won 17 out of 22 cases or 77% of the time. It's clear who has the upper hand, making it hard to take seriously those who suggest the government has a hard time making its case under the current legal standard of the law before the courts.

- Enforcement of the law matters. When the government challenged more cases during the second decade, its winning percentage actually went up, not down. This supports the notion that burden shifting is unnecessary as there are clearly additional cases that can be brought under the law. If more cases were brought and the winning percentage went down, then perhaps critics could argue that mergers that should be blocked aren’t being blocked. Instead, the data suggests the enforcement agencies need the courage and additional resources to challenge mergers it finds problematic.

- Courts pay attention to evolving economic thinking.The 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines recast the way the antitrust agencies would evaluate horizontal mergers. While not a change in statute, the Shapiro and Shelanski make a credible case for how changes in the guidelines shaped the thinking of the courts. Post-change, the government not only stepped-up enforcement but also used the updated guidelines to bring -- and win -- more cases. This demonstrates that the antitrust laws are both sufficiently flexible to incorporate evolving economic understanding and that precedent established by the court does not serve as an immovable force.

Taken together the government’s successful record of blocking mergers makes it hard to credibility support changes to the statutory legal standard by which mergers are reviewed or to consider shifting the burden away from the government to the merging parties. The overwhelming majority of mergers are pro-competitive, that is not debatable. For the handful of transactions that raise concerns, the government possess a solid legal framework and influence over the way courts think about economics. The one thing it arguably needs is more resources to enforce the law.

Additional reading:

- U.S. Antitrust Agencies Vertical Merger Guidelines (2020)

- Unlocking Antritrust: Evaluating Horizontal Mergers

- Unlocking Antirtust: 3 Reasons Why Simplicity is Antitrust's Greatest Strength

- Unlocking Antitrust: Acquisitions of Nascent Firms

About the author

Sean Heather

Sean Heather is Senior Vice President for International Regulatory Affairs and Antitrust.